Simon Milyus Rosenthal

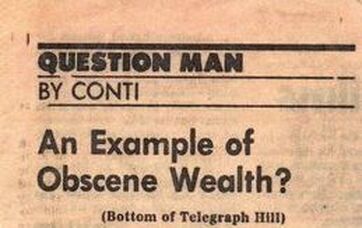

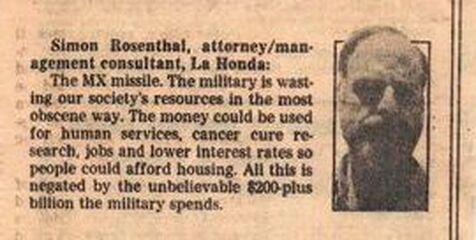

Simon (“Si”) Milyus Rosenthal, public interest lawyer and former dean of New College School of Law, dedicated his career to seeking justice for marginalized people, improving legal services and programs for low-income clients, and working for peace. Throughout his life, Si was adamantly antiwar. When asked by a San Francisco Chronicle reporter for an “example of obscene wealth” in 1983, Si responded: “The MX missile.”

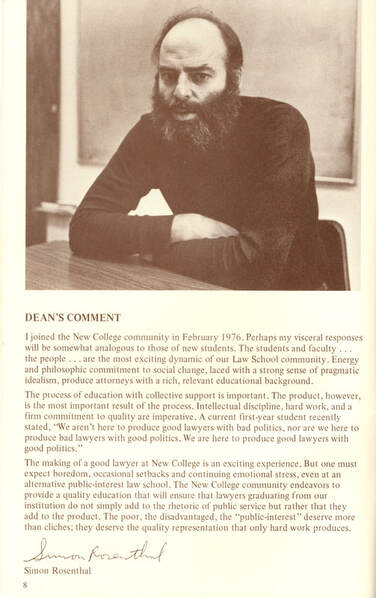

Si believed the public interest is advanced by fighting for individuals’ rights under the law and by trying cases that set precedents and help bring institutional change for the advancement of all people’s interests. “The making of a good lawyer,” wrote Si in 1977, takes “intellectual discipline, hard work, and a firm commitment to quality. The poor, the disadvantaged, the ‘public-interest’ deserve more than cliches; they deserve the quality representation that only hard work produces.”

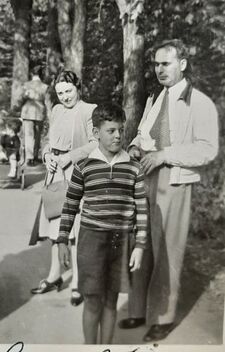

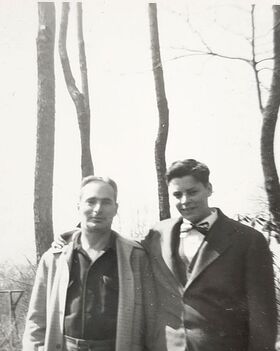

Born on March 11, 1935, in New York City, Si was the only child of Louis M. Rosenthal and Rebecca (“Ruth”) Wittes Rosenthal. Louis was a pioneer in the manufacture of radio tubes and extremely long-lasting light bulb, which he and partners produced and sold from a factory in Hoboken, N.J. In the late 1930s, the Rosenthals moved from Manhattan to Teaneck, N.J.

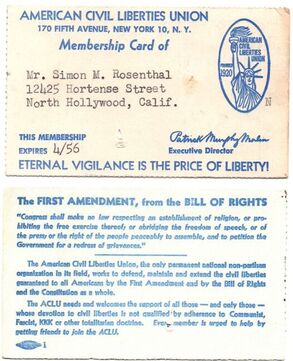

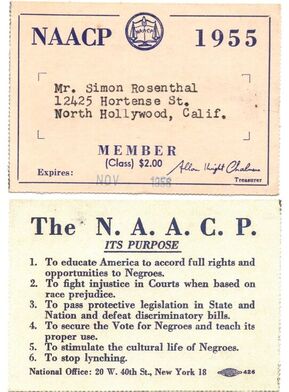

From an early age Si was avidly interested in international politics and human rights—news editors began publishing his letters when he was only 15 years old—and Si joined the NAACP and the ACLU in 1955. Shortly after Si graduated from Teaneck High School, he and his parents moved to Los Angeles to be near Louis’s family: his parents chose not to tell Si that Louis had been suffering from leukemia for several years. Si’s father died on Nov. 22, 1954, a devastating shock for Si, who had just started his first year of college.

|

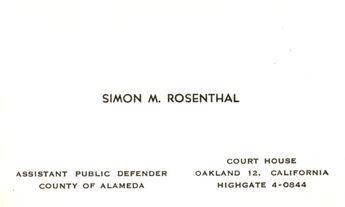

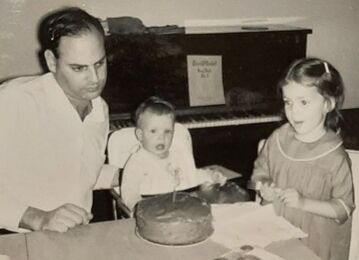

Si earned his bachelor’s degree in business from the University of Southern California in 1957 and his law degree from UCLA in 1960. During law school, he clerked for the Alameda County public defender’s office. An admirer of the Beat writers, Si drove across the country while awaiting his Bar exam results. In Chicago, he met and fell in love with Julia Ann Karrer, a nurse from Dublin, Ohio. Si was admitted to the California Bar in January 1961, began working as a public defender for Alameda County, and married Julia on April 22. |

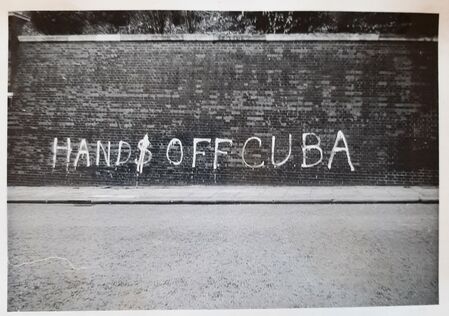

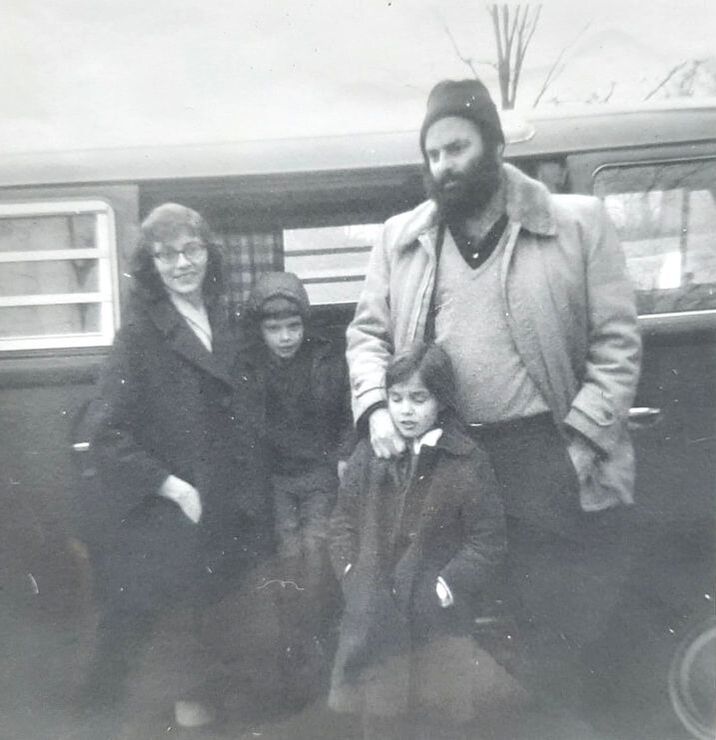

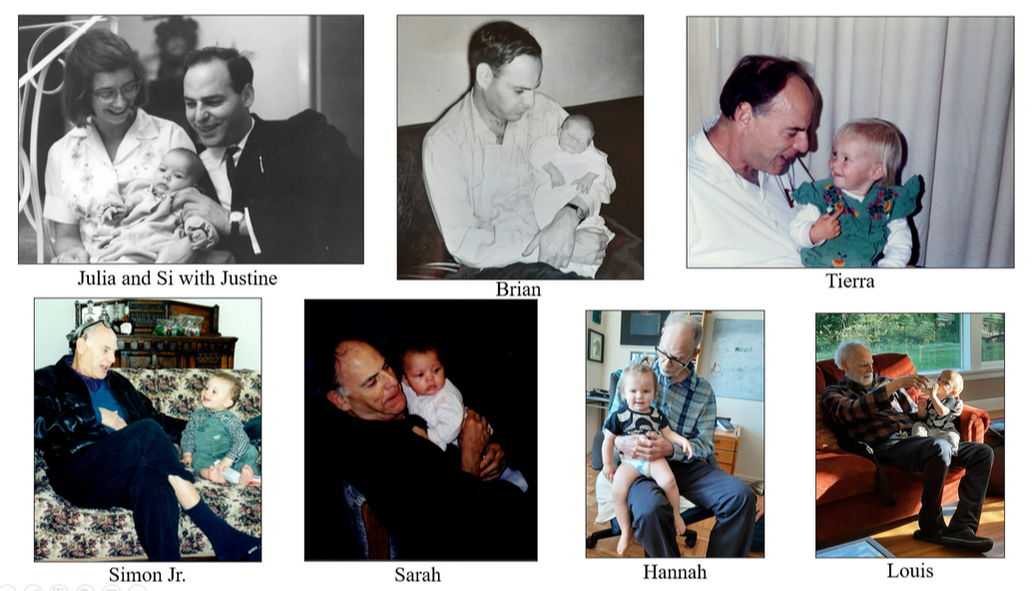

Si joined the National Lawyers Guild and the National Legal Aid & Defender Association (NLADA), speaking at conferences and publishing op-ed pieces. After 18 months with the public defender’s office, Si took Julia on a camping trip across Europe. The couple sailed to Denmark, bought a car and drove around northern Europe, took a guided tour of the U.S.S.R., and then drove west to Spain. By September they were settled in London, where Si helped lead peace marches during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Rosenthals’ daughter, Justine Lou, was born in October.

|

At the end of 1962 they returned to California. Si joined a law-school classmate (Herbert M. Porter) at his law office in Watts, but the partnership lasted only six months. Si and his family moved north to San Francisco. As an attorney with the Legal Aid Society of Alameda County at its Oakland office, Si was a pioneer in the War on Poverty (announced by President Lyndon Johnson in his 1964 State of the Union address and enacted on Aug. 20, 1964). In addition to helping with day-to-day legal problems, Si wanted to bring test cases to the appellate courts in order to change precedents, filing suit against those who preyed on migrant workers and the poor, such as collection agencies. “In civil law, with no judicial right to counsel yet,” Si said in 1965, there are “many types of statutes which have a particularly onerous application only as to ‘indigents.’ I believe it is up to the legal services projects to provide some appellate test-case law in these areas.” To raise funds for legal aid projects, Si applied for a grant under the War on Poverty program; it was awarded twice the money he’d requested.

|

|

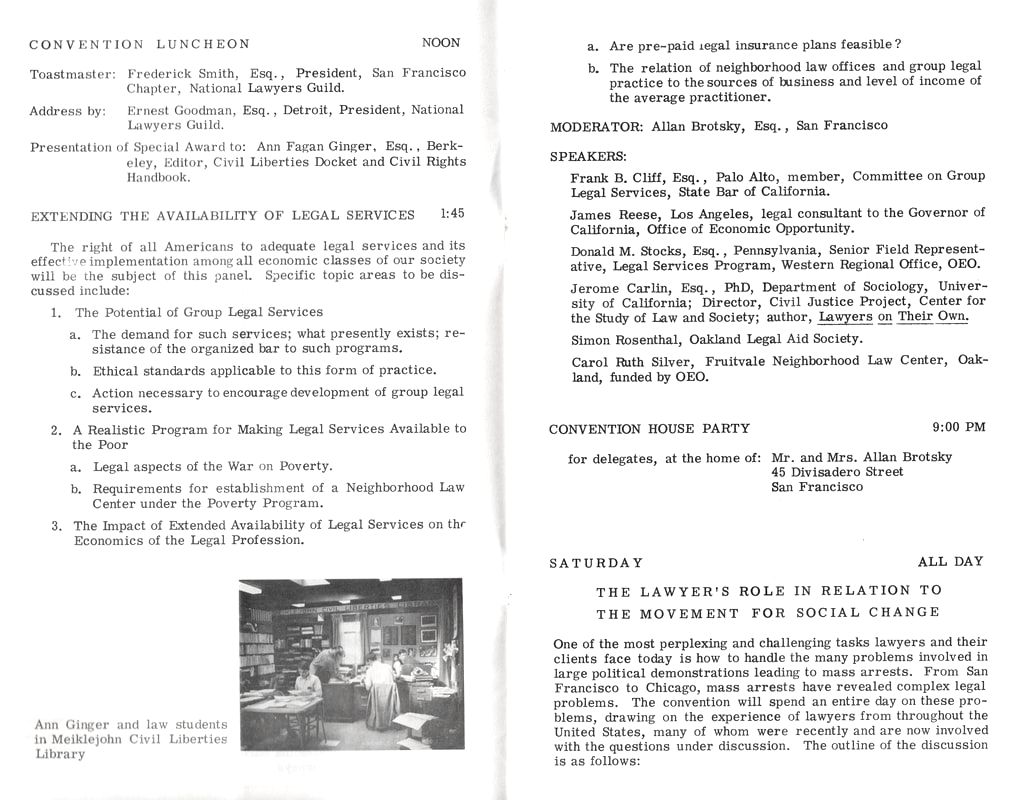

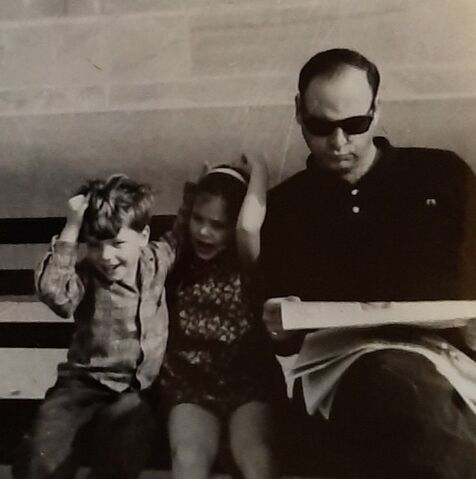

Si and Julie’s son, Brian Henry, was born in March 1965. Si was an active member of the National Lawyers Guild and among the speakers at its convention in November 1965. At a time when the brand-new national Legal Services program was battling resistance from local and state Bar associations, Si and many members of the Lawyers Guild were championing federally funded neighborhood legal aid offices.

“This is an exciting thing,” Si said at the 1965 convention. “Not as dramatic as going down south and fighting for civil rights, civil liberties and human freedom. But it is fighting for human freedom in another sense of the phrase. If an individual is denied an attorney, is denied legal services when their children are in jeopardy in a child-custody suit or a juvenile action, this is a tragedy. It’s a tragedy for the individual, for our society, for the Bar." Thanks to Pacifica Radio Archives, we can hear KPFA radio's broadcast of Si's speech at the National Lawyers Guild convention in 1965 (program with list of speakers below).

We are very grateful to Pacifica Radio Archives! |

|

One of Si’s mentors was Ann Fagan Ginger, founder and executive director emerita of the Meiklejohn Civil Liberties Institute in Berkeley.

Among Si’s more radical friends was Oscar Zeta Acosta (the “Brown Buffalo”), and Si persuaded him to join Legal Aid as an attorney. Acosta became a leader of the Chicano Movement, and he dedicated his first novel, The Autobiography of A Brown Buffalo (Straight Arrow Press, 1972), to Si. |

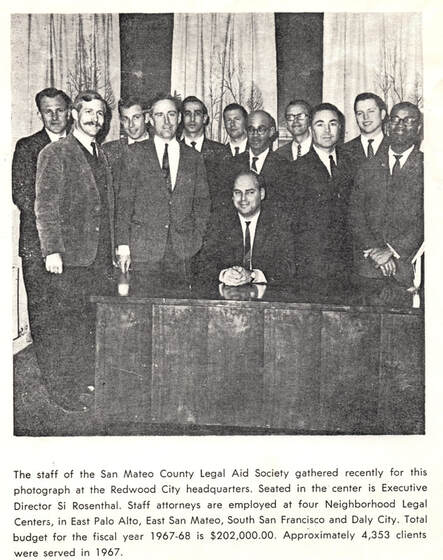

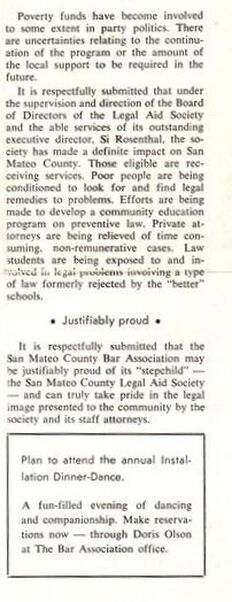

In 1966 Si was named the first full-time director of the Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County, based in Redwood City, Calif., where he opened four regional offices. “There must be some concept of equal justice that goes beyond the written word, but goes into practice," said Si. "Because why should anyone respect the law, when the only contact he ever has with the law is at the end of a policeman’s club? Or some strange-looking papers that have been thrust in his hand, called a Summons and Complaint? The anti-poverty program is providing us with an opportunity to make justice more of a realistic concept.”

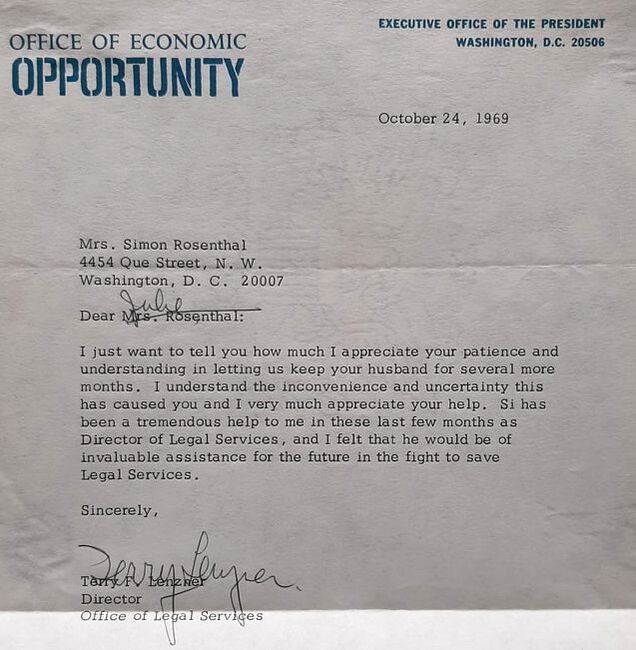

From 1968 through 1970, Si worked in Washington, D.C., as national deputy director and chief of the evaluation division of the Office of Legal Services, then part of the former U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). The OEO’s Legal Services Division employed 3,000 attorneys in funded programs around the country.

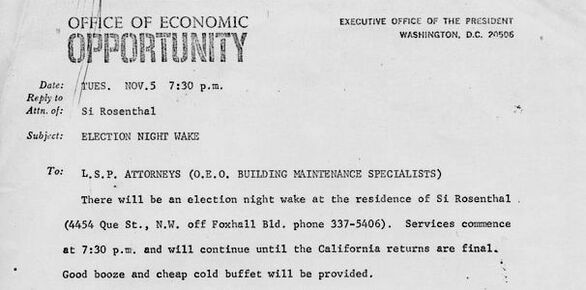

Ever outspoken, Si invited the Washington Legal Services staff to an election-night “wake” at his house on Nov. 5, 1968. When Richard Nixon took office as President Jan. 20, 1969, he began to defund and dismantle the OEO, appointing Donald Rumsfeld as its director in May 1970. The appointment of Rumsfeld signaled doom to Si and his boss, Terry F. Lenzner.

Si resigned later that year, although his departure was delayed. In a letter to Julia dated Oct. 24, 1969, Lenzner wrote, “I just want to tell you how much I appreciate your … letting us keep your husband for several more months. Si has been a tremendous help to me in these last few months as Director of Legal Services, and I felt that he would be of invaluable assistance for the future in the fight to save Legal Services.” Less than a month after writing the letter, Lenzner himself was fired by Rumsfeld.

In a New York Times article on April 28, 1971, Lenzner was quoted: “Mr. Lenzner said that Donald Rumsfeld, then director of the poverty agency, had ordered Mr. Lenzner to discharge Mr. Rosenthal because of information in the file that Mr. Rosenthal had subscribed to radical magazines and had belonged to the Lawyer’s (sic) Guild, a left-leaning legal organization.”

Ever outspoken, Si invited the Washington Legal Services staff to an election-night “wake” at his house on Nov. 5, 1968. When Richard Nixon took office as President Jan. 20, 1969, he began to defund and dismantle the OEO, appointing Donald Rumsfeld as its director in May 1970. The appointment of Rumsfeld signaled doom to Si and his boss, Terry F. Lenzner.

Si resigned later that year, although his departure was delayed. In a letter to Julia dated Oct. 24, 1969, Lenzner wrote, “I just want to tell you how much I appreciate your … letting us keep your husband for several more months. Si has been a tremendous help to me in these last few months as Director of Legal Services, and I felt that he would be of invaluable assistance for the future in the fight to save Legal Services.” Less than a month after writing the letter, Lenzner himself was fired by Rumsfeld.

In a New York Times article on April 28, 1971, Lenzner was quoted: “Mr. Lenzner said that Donald Rumsfeld, then director of the poverty agency, had ordered Mr. Lenzner to discharge Mr. Rosenthal because of information in the file that Mr. Rosenthal had subscribed to radical magazines and had belonged to the Lawyer’s (sic) Guild, a left-leaning legal organization.”

|

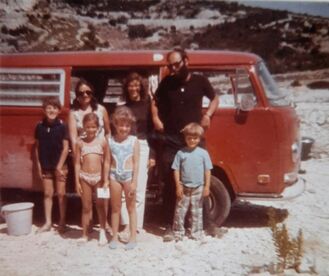

Si and his family took a camping/driving trip through Europe, and they were in London when Si learned his former boss had been fired. Si sent Lenzner a congratulatory telegram.

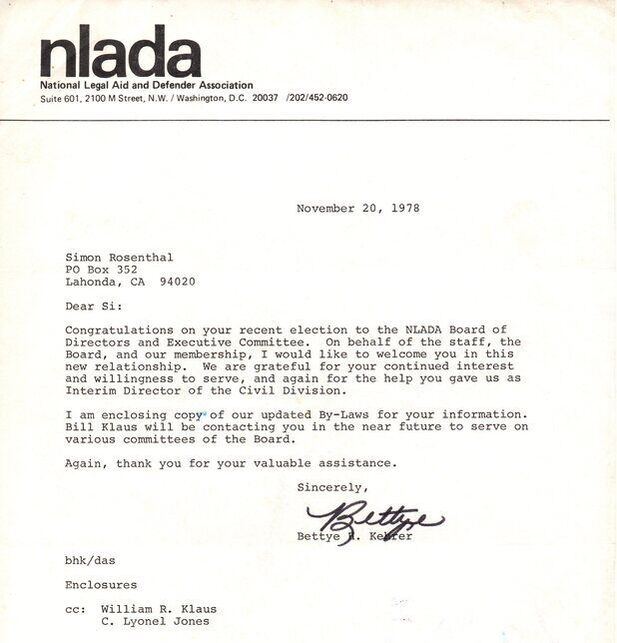

In December the Rosenthals returned to the San Francisco Bay Area, and Si rejoined the Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County, working as director from 1971 until 1975. He also chaired the National Project Advisory Group of Legal Services Programs in 1972 and 1973; served in local and national bar associations, and was on the NLADA’s board of directors and executive committee from 1973 to 1975, and again in 1978. In September 1978 Si wrote "Legal Services ... Revisited" for the NLADA's quarterly magazine, Briefcase: "The last four months have been an interesting opportunity to review the many changes that have occurred in the legal services community during my three year absence," he wrote. "The idealism is missing..." [read full essay] Si was elected to the Meiklejohn Civil Liberties Institute’s board of directors in 1985, along with Ying Lee-Kelley, the Hon. Thelton Henderson, and Linus Pauling. "Maybe I'm over-personalizing my anger at the madness of the militarism in this country. It's a threat to me, a threat to my family," Si said. "Our children. It's a threat to all children." |

|

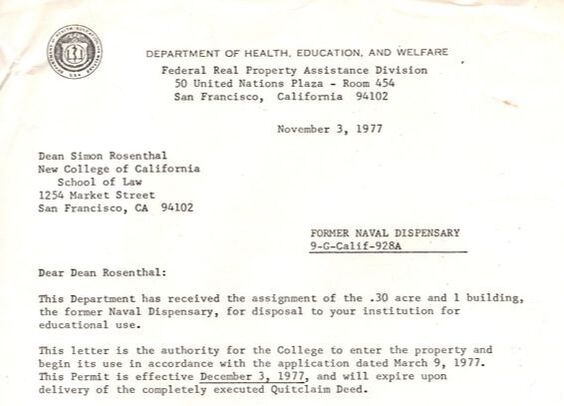

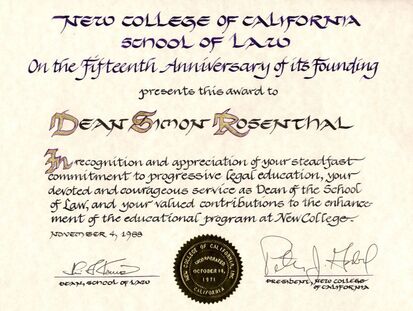

By 1973, Si and Julia’s marriage was ending; they divorced in December. Si moved to La Honda and was named dean of the New College of California School of Law in San Francisco, a position he held from 1976 to 1978. At New College, Si developed its accreditation application and secured a real estate grant from the U.S. government that was crucial to the college’s financial stability. After stepping down as dean, Si continued to serve on the New College board of trustees. He moved from La Honda to San Francisco, and in 1981 he joined the NLADA’s civil division technical assistance committee.

|

From 1974 and throughout the ’80s, Si worked as a consultant for Legal Services and traveled around the country for the national office, evaluating programs and giving management training and coaching.

He enjoyed teaching and was an adjunct professor at Stanford University, Cañada College, and

Catholic University Legal Aid Directors Management Training.

“Mr. Rosenthal is a gentleman of particularly enlightened views,” wrote James Leavitt, Administration of Justice Program, Cañada College, in 1974. “A unique combination of administrative abilities, professional expertise and practical political experience.”

He enjoyed teaching and was an adjunct professor at Stanford University, Cañada College, and

Catholic University Legal Aid Directors Management Training.

“Mr. Rosenthal is a gentleman of particularly enlightened views,” wrote James Leavitt, Administration of Justice Program, Cañada College, in 1974. “A unique combination of administrative abilities, professional expertise and practical political experience.”

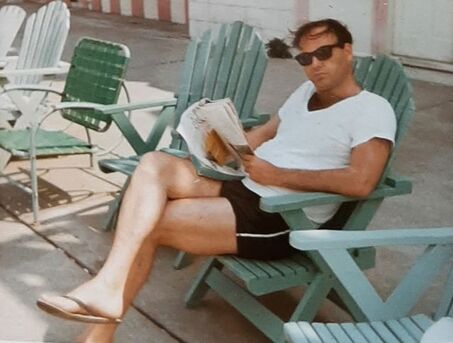

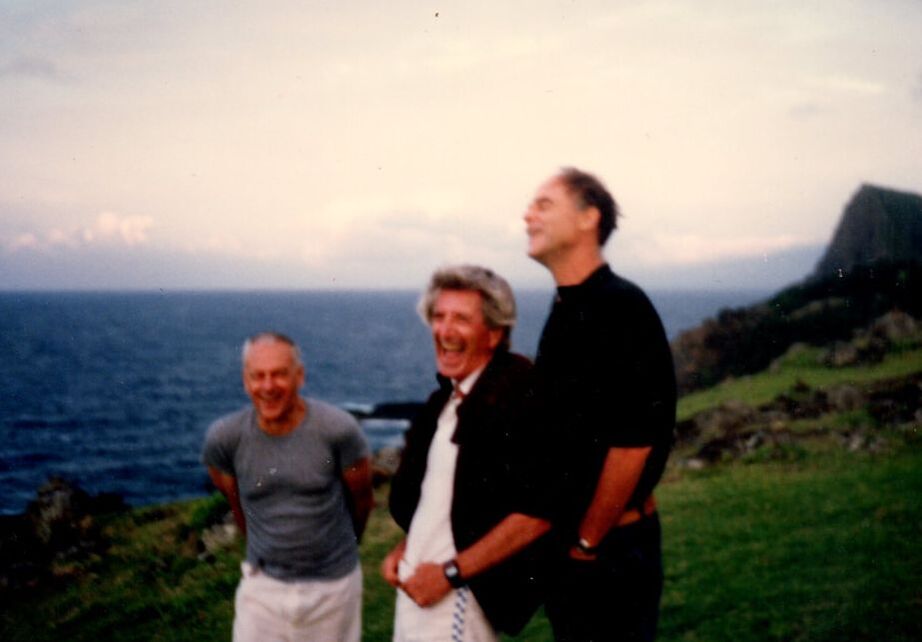

In his free time, Si traveled as often as he could, savoring restaurants, music, theater, the arts, and the company of his friends and family. He met his second wife, Emily Brewton Schilling, in 1996. Si and Emily started life together in a studio apartment on Maui, then moved around: northern California; New York City; Sarasota, Fla.; and back to New York City in 2011.

In May 2021 they moved to northwest Oregon to live near Si’s children and grandchildren. After a short illness, nursed at home by his family with hospice support, Si died of natural causes on Dec. 27, 2021.

He is survived by his wife Emily; his daughter Justine (Janine Johnson) of The Sea Ranch, Calif.;

his son Brian (Joanna Wagner) of Scappoose, Ore.; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Si’s archives are in the National Equal Justice Library, Georgetown University School of Law, Washington, D.C.

In May 2021 they moved to northwest Oregon to live near Si’s children and grandchildren. After a short illness, nursed at home by his family with hospice support, Si died of natural causes on Dec. 27, 2021.

He is survived by his wife Emily; his daughter Justine (Janine Johnson) of The Sea Ranch, Calif.;

his son Brian (Joanna Wagner) of Scappoose, Ore.; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Si’s archives are in the National Equal Justice Library, Georgetown University School of Law, Washington, D.C.

References, notes, further reading

Acosta, Oscar Z. The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo. San Francisco: Straight Arrow Press, 1972.

Acosta, Oscar Z, and Ilan Stavans. Oscar "Zeta" Acosta: The Uncollected Works. Houston, Tex: Arte Público Press, 1996. p. 153.

Johnson, Earl Jr. Justice and Reform: The Formative Years of the American Legal Services Program. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, revised ed. 1978. (Originally published in 1974 as Justice and Reform: The Formative Years of the OEO Legal Services Program.)

Lund-Montaño, Camilo. Out of Order: Radical Lawyers and Social Movements in the Cold War. Doctor of history dissertation, np, University of California, Berkeley, 2019. p. 62; n83, p. 62

“Neighborhood Law Offices: The New Wave in Legal Services for the Poor.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 80, no. 4, The Harvard Law Review Association, 1967, pp. 805–50, https://doi.org/10.2307/1339383.

The interment of Si’s ashes, under a river-stone grove created by the family, took place privately on Aug. 14, 2022.

Essay: 'The Heartbreaking Luxury of Home Hospice Care' by Emily in Broad Street Review.

To the extent possible under law,

Emily Brewton Schilling

has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to

Simon Milyus Rosenthal biographical text.